Hippodrome

Thursday morning, just past six. Training always begins at sunrise. The place feels dormant, and not just because of the early hour. From the stands – a simple concrete structure dotted with white plastic chairs – I overlook the racetrack and the narrower training course, where the sand lies deeper. Between them, old pine trees stand, survivors of the civil war. Beyond, Beirut’s high-rises stretch into the sky. Two horses gallop past. The trainer watches from a modest shelter on the sidelines. I’m allowed to time the runs. The first race of the new season is set for Sunday. Later, George, one of the racehorse owners, shows me the stables and proudly displays the prizes he has won. By trade, he trains bodyguards, among other things. It’s a world of men, both at the training grounds and on race day.

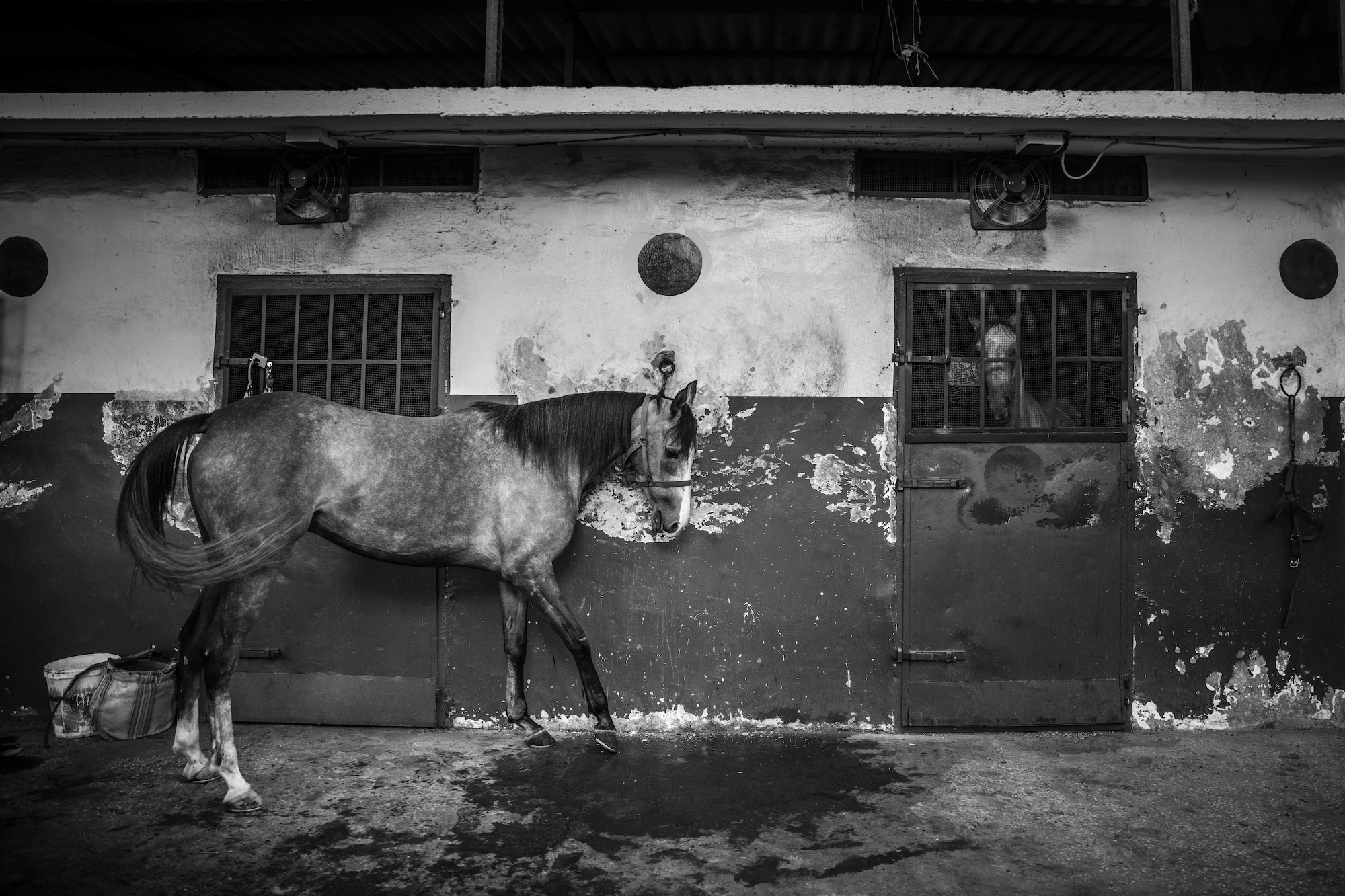

Together with the adjacent Horsh Beirut park, the Hippodrome forms the last large open space in the heart of the city. Spanning 20 hectares, the grounds include not only the racetrack, training course, and stands but also offices, stables, and a paddock – where horses are presented to the audience before races – as well as the betting booths. The land belongs to the city, while the races and betting are overseen by Sparca (, the nonprofit organization. Lebanon is the only country in the Arab world where betting is legally permitted. Races are held on three Sundays a month, depending on horse availability – except during the height of summer.

The Hippodrome is woven into Beirut’s collective memory, a symbol of Lebanon’s history – its glamour and its crises alike. It remains one of the rare places in the country where religious communities converge, though with distinct roles: the horse owners are Christian, the stable hands Muslim, while the jockeys are predominantly from the Dom ethnic group. Nabil Nasrallah, a qualified engineer, began working at the Hippodrome in 1971. He has served as its director since 1976, having previously studied, among other places, in Karlsruhe.

Horse racing was first introduced to Beirut in 1880, when the city was part of the Ottoman Empire. In 1918, Alfred Sursock – of the prominent Sursock family, known for landmarks like the Sursock Museum and Sursock Palace – financed the construction of the Hippodrome. The project included a casino, which, following the collapse of the multiethnic empire, became the headquarters of the French Mandate authorities. Since Lebanon’s independence, it has served as the residence of the French ambassador. Inaugurated in 1921, the Hippodrome was an elegant venue with a magnificent grandstand. By the 1960s, it had become one of the most frequented racetracks in the world, hosting races twice a week, 52 weeks a year. Visitors included the Shah of Iran, the Saudi royal family, and the King of Jordan. Beirut was the entertainment and business hub of the Middle East.

The civil war that followed was devastating. The Hippodrome lay along the Green Line, which divided Beirut into Christian and Muslim sectors. On 13 May 1975, it was closed, only reopening for racing in the spring of 1978. Throughout the 15-year war, races were held intermittently, despite repeated disruptions. Even in 1982, when the Israeli army occupied the Hippodrome and bombed the grandstand, suspecting it to be a hideout for Palestinian fighters, racing endured. In a rescue operation, most of the racehorses were successfully relocated to the Bekaa Valley.

After the civil war, the city administration embarked on an ambitious reconstruction project but later withdrew funding. While Beirut’s (construction) economy boomed, the concrete grandstand from 1992 remained a rudimentary structure. The ongoing economic crisis has also taken its toll on the racetrack, as has the illegal betting industry. Nabil Nasrallah has drafted plans for a new Hippodrome, envisioning an expansive park within the racetrack – a venue for concerts and festivals, complete with restaurants and cafés. His plans include an elegant new grandstand with a jockey club, air-conditioned VIP boxes, a show-jumping arena, and modern stables. The site itself has attracted considerable interest: Hezbollah has proposed building a cemetery for its martyrs here, while others have suggested a shopping centre or luxury apartments – the usual ventures. So far, Nabil Nasrallah has successfully fended off these competing interests – and remains steadfast in pursuing his vision.